Socially responsible investing, or SRI, is an investment strategy that has been gaining popularity over the past 20 years. An investment is considered socially responsible owing to the nature of the business the company performs. It is supposed to not only bring a financial return, but also social and environmental good.

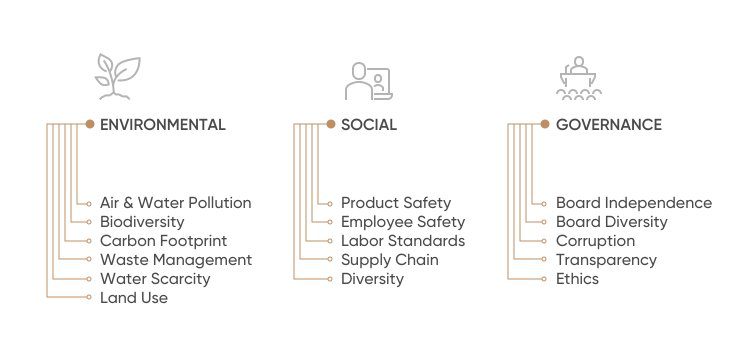

The three main factors that underlie the measurement of the sustainability and ethical impact of investment are sometimes summarised under the heading of ESG issues: environment, social justice and corporate governance.

Simply put, SRI is an investment strategy that seeks both financial return and social good. Many involved in SRI investing avoid companies perceived to have negative social effects, such as fast food, alcohol, tobacco, gambling, weapons, pornography and fossil fuel production.

Socially responsible investors choose to stick to the companies that do their business in positive and thoughtful ways. Although the majority of investors aren’t socially responsible yet, their number is continuously growing.

According to the US SIF, an organisation for socially responsible investors, the total investments in managed funds in the US that apply SRI strategies has grown to almost $12.0 trillion in 2018, representing a 38% increase from $8.7 trillion in 2016. In comparison, in 1995, SRI assets accounted for $1 trillion.

How did it all begin?

The roots of SRI go centuries back to the Religious Society of Friends, also known as the Quakers. Back in 1758, the group’s Philadelphia Yearly Meeting prohibited its members from participating in slave trading or weapons investing, as these were viewed as harmful acts towards society.

Throughout the years, some of the best-known applications of socially responsible investing were religiously motivated: investors would avoid “sinful” companies, like those associated with liquor, tobacco and gun production.

John Wesley, an English theologian, evangelist and leader of Methodism, was one of the earliest adopters of SRI. In his sermon “The use of money”, he outlined basic tenets of social investing, such as not harming your neighbour through your business practices and avoiding industries that can harm the health of workers.

Typically, SRI tends to mimic the social and political climate of the time. In the 1960s, investors were primarily concerned with contributing to matters, such as civil rights, gender equality, labour issues and the anti-war movement. As an example, Martin Luther King Jr. played a large role in raising awareness for the civil rights movement, calling companies that opposed the matter socially irresponsible.

As awareness of climate change and global warming has grown in recent years, socially responsible investing has largely shifted toward businesses that positively impact the environment by creating new harmless energy sources or reducing emissions.

The state of socially responsible investing in 2019

In 2007, the first green bond, a €600 million equity index-linked security, was issued by the European Investment Bank. All the proceeds were used to fund energy efficiency and renewable energy projects. Shortly after, the World Bank followed the trend, and over $155 billion worth of corporate and public green bonds had been issued by 2017. Later, the Seychelles government issued the first-ever blue bond, a $15 million bond to fund sustainable fisheries and overall marine protection.

The success of these new financial instruments represents the fact that investors are becoming more conscious of both environmental and social consequences of the decisions made by companies and governments. The result has been an increasing demand for integrating ESG factors into investment decisions. According to the US SIF report, in early 2018, $11.6 trillion of all professionally managed assets in the US were under ESG investment strategies.

How to become a socially responsible Investor

Socially responsible investors encourage corporate practices that stand up for human rights, diversity, consumer protection and environmental stewardship. Some avoid businesses involved in tobacco, alcohol, pornography, weapons and gambling. It is believed that by exerting collective investment power, investors can bring about positive changes to the environment and communities, achieving social benefits along with the financial reward.

When choosing a socially responsible investment, investors tend to promote a number of various goals, such as:

- Peace promotion. These investors won’t invest in a war in any way, avoiding companies that profit from the conflict in foreign regions or produce weapons.

- Health promotion. These investors mainly reject investments in businesses that sell alcohol or tobacco or produce dangerous products, like GMO.

- Morality promotion. These investors continue the time-honoured practice of eschewing so-called ‘sin industries’ that include various types of enterprises like pornography, gambling and contraception.

- Cleaner environment. ‘Green’ investors prefer companies that don’t harm the environment, invest in companies that minimise the carbon footprint of their products.

- Social justice. These investors refuse to invest in business and countries with a record of human rights violations, looking for companies that provide their employees with proper working conditions and fair wages.

As all investors have different values and standards, their investment decisions may also vary and yet be considered socially responsible. If you are interested in joining this rapidly growing “conscious” community, you have to choose investments that go in line with your morals and ideas, as well as serve your financial goals.

When getting started, you can choose from a variety of strategies, including negative screening and positive investing. ‘Negative screening’ is the refusal to invest in companies that don’t meet your social norms, while the ‘positive investing’ takes a more active position by choosing to invest in companies that adhere to your personal values.

Read the full article at capital.com